HIGH SCHOOL

The Peñasco High School class of 194l, of which I was the

Salutatorian, consisted of sixteen graduates. It was May 25, 1941, graduation

day! I was fifteen years of age and the oldest boy in a family of six boys and

one girl. Our father, Gregório Chacón, a veteran of World War I action at

Muese-Argonne had been in and out of the Veteran's Hospital since 1938 and

unable to work at his usual occupation, that of contract mail carrier from the

Railroad Station at Embudo to Peñasco, could not be there, but my mother was. (The contract was shared with Ricardo

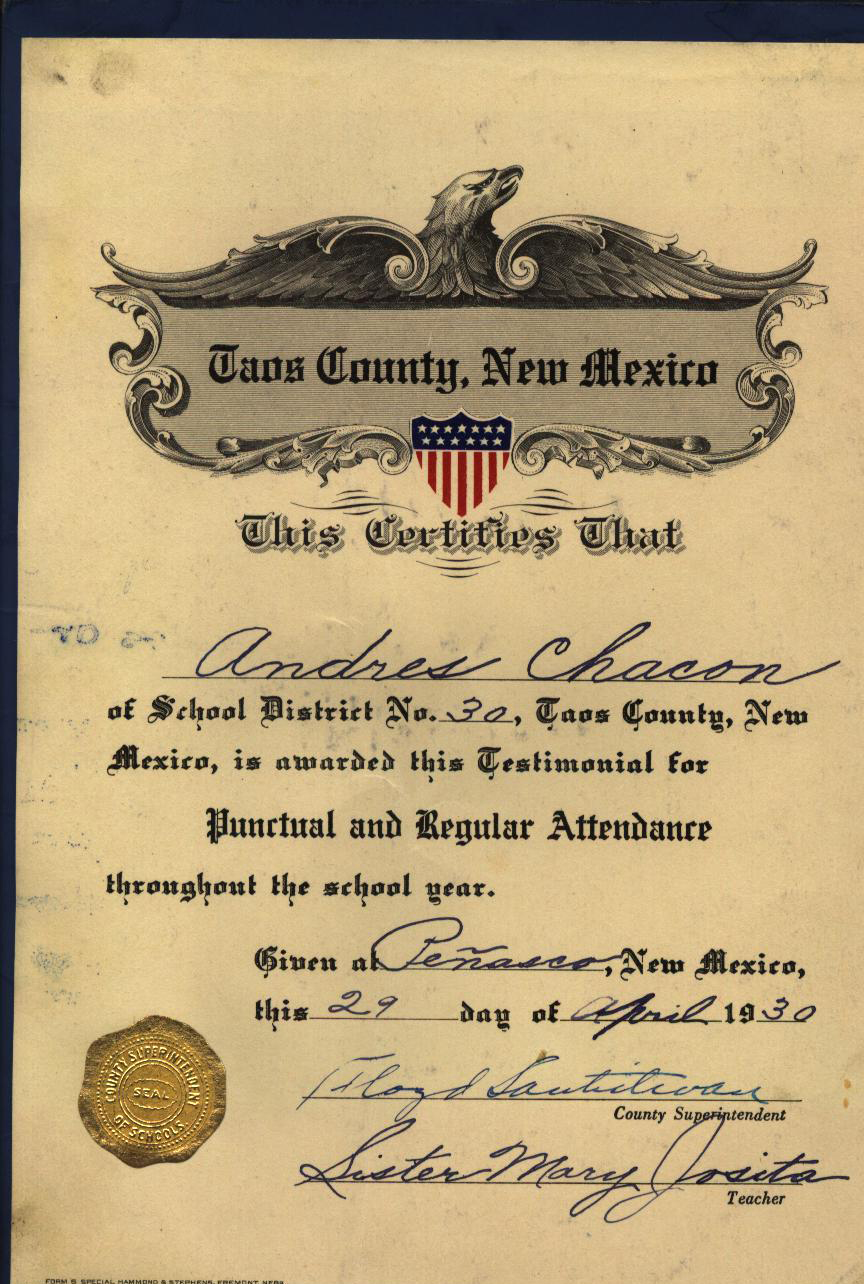

Duran, my (to be) wife's father.) My mother made sure I got to school every day and on time, see below.

Perfect Attendance - Not Perfect Conduct!

After giving a very short Salutatory address I sat down while the Valedictorian, (he edged me out for this distinction because of my grades in "deportment"), gave a very long address mostly about how the sixteen graduating seniors from PEN-HI were going forth from that day on to save the world! Having heard that address several times, while Sister Maura held me to my seat by my left ear lobe; I was not then listening to Benedict Valdez. Instead I was contemplating my fifteen years in Peñasco. I was leaving the very next day. Leaving to find my fortune in the outside world. A world in which, in response to a question by my chemistry teacher, Mr. Bibo, I had ventured that there could possibly be a total of $100,000 in cash out there!

Scenes In Peñasco Valley

|

La Jicarita & Truchas Peaks

La Jicarita Dominates The Peñasco Valley

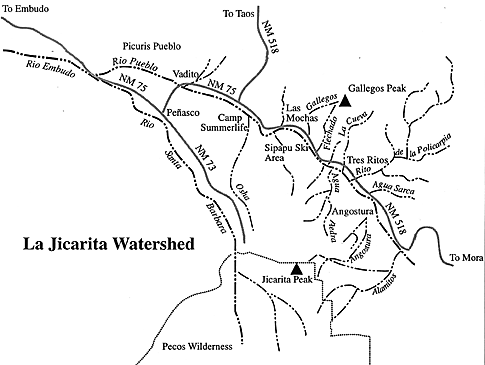

Map Of The Peñasco Area - (Heaven)

Work was a very important part of my daily life in Peñasco. As the oldest of six boys I was the first trained to do the farm work and grew accustomed to the long hours during the short growing seasons. Because my father became ill it fell upon me to train the others. At age of eight I could handle a team of draft horses, affectionately named "el tuerto y la china" not only to plow the fields but to hitch to a wagon to harvest the crops. At age of ten I could harness the team and did so to haul wood during the fall in preparation for the severe winters during which firewood was our only source of energy. These were pre-rural electrification days.

At harvest time we thrashed wheat and took it to the mill in Mora where we paid for the milling with more wheat. The bran was used for breakfast cereal served with fresh cream skimmed from gallons of milk obtained from eight cows that we milked twice a day. The skimmed milk was fed to our hogs which in turn provided ham and bacon as well as chicharones during the cold months. There was no refrigeration in the rural areas of the nation in those days.

We had no money, we lived in a barter economy. My father received a Veteran's pension that was less than $80.00 per month. That was our total money income, however, we never went hungry, we did not know that there was a depression. Our clothes were used, that is second hand. They came to us through the local priest, Father Peter Kuppers, who every November had us cut Christmas trees which my father, the mail carrier, took to the train station and the good Father sent to parishes "back east" who in turn responded by sending us their used clothes. It seems everyone "back east" wore knickers in those days, those were the only kind of trousers we ever got! Since no self-respecting Peñasco kid would be caught wearing knickers, the improvising that went on was ingenious. You lucked out if you got a two-knickers suit from Father Kuppers. Your pants looked fairly respectable when you could cut the legs off one pair and sew them on to the other pair, that was better than when you had to do that with two different kinds of materials or colors. The fights among the boys at school were over the denials of wearing knickers made into regular trousers!

About the only cash we needed was for salt, pepper, sugar and gasoline which sold at 16 cents a gallon. The gasoline was for the Ford pick-up truck that my father used to bring the mail in from Embudo for the last six years of his service, prior to that he used horse and buggy.

Under the blue cap and gown I was wearing at the graduation ceremony was my first tailor made suit. It had been ordered from the Progress Tailoring Co. of Chicago made to order for a total price of $39.95. I had worked every Saturday my last year of high school to buy that suit. Early each Saturday I would get up at 5:00 AM, hitch el tuerto y la china and go after a load of wood. Every other Saturday the load of wood I brought I was allowed to sell. At $2.50 per load, it took sixteen loads of wood to buy that suit. It had everything; flaps on all pockets, watch pocket, shoulder pads, vest, etc., and it was a black pin-stripped number too. I was proud of that suit, so proud that I kept it until I went to Seattle in 1943 and I wore it to the YMCA one Sunday after mass. Everyone laughed at me, so I did not wear it again, but this is getting ahead of my story.

Still at the graduation ceremony I was thinking of other flowers that I had smelled along the way. Learning to do hard work was only one.

There were some flowers that I wished now I had taken some time to smell along the way. While I was plowing fields, milking cows, harvesting crops or doing chemistry lab experiments, (I was already interested in science) my contemporaries, who were always at least three years older than I, were busy doing other things. George and Daniel Vasquez were brothers and Esteban Sanchez was their cousin. All three played the guitar. That was practically all the two Vasquez brothers did, Esteban worked as a day laborer for us during the harvest season for fifty cents a day. I tried the guitar once, George tried to teach me but gave up saying I had "fat" fingers. I did. I still do. Work with the axe, the pick, the shovel and the hoe produce big biceps, big wrists, fat fingers and a short frame, I am only five foot seven. I gave up trying to play the guitar. I wish now that "I had taken the time to smell the flowers".

When George and Daniel made fun of me for working, they were only getting even with me for something that happened way back in 1936. My father, being the mail carrier and having contact with the outside world, brought the first radio to Peñasco, that is other than the Anglo Forest Ranger. Like everything else we had, it was used. Not quite a crystal set but almost. It was battery run and it had a ground wire which my father ran out through the window and stuck into the ground, of course! When the Vasquez brothers wanted to know what the wire was for I volunteered that it was to hear the voices from the other world. They believed it, and it wasn't until years later that they realized I had given them a snow job. I was nine at the time. That was also the year that Senator Bronson Cutting died and left my father $1,000 in his will! Everyone in Peñasco knew then that we were rich! With that money we built a new house, yes we built a new house! The making of the adobes was contracted out at $30.00 a thousand. The albanil and the finish carpenter got $2.00 per day, all others got fifty cents a day. Since my father ran the mails two weeks out of each month, I was in charge of the work crew while he was gone. I was now ten. We must have given the workers all they could eat because I remember they came in for breakfast of eggs, home-made bacon, chaquewe, home made bread or tortillas and all the milk they could drink. But I remember I was in charge even then because I told each of the workers when they could come into the kitchen and when it was time to start work. I was already "el patron". I must also have been enjoying it too. I remember once that one of my cousins had been "soldiering" and I told my father about it. He dismissed him on my say so. Later I was to pay for that one. I must have learned about construction and work crews from this experience as we shall see later. The house we built still stands in Peñasco. It is an adobe with a galvanized tin roof, the kind that caught Robert Redford's attention when he selected Truchas for filming the movie THE MILAGRO BEANFIELD WAR.

It was a long valedictory address! I also thought about why I was so much younger than the rest of my classmates. That was my mother's doings. Even though she had gone no further than the eighth grade, my mother, Emilia Martinez Chacón, had been a school teacher and she started me in school at age four at the insistence of the Dominican Sisters, who ran the public schools in Peñasco at the time. They wanted mother to teach and the only way she could was if I would be allowed in school, so I started at age four. Later, I made the seventh and eighth grades in a single year, so now in 1941 I was graduating at age 15, my classmates ranged in age from 18 to 24.

As I entered the church, where graduations were held in those days I noticed that the mountains were covered with snow. We had 12 inches of snow on May 20th that year but now it was a nice sunny day and as I looked up towards the Rio Santa Barbara I got a nostalgic feeling. I knew I was going to miss my summer stumping grounds. Sure, early in the Spring there was the plowing and the planting and in the fall there was all the harvesting to be done, but in late Spring there were the fishing trips to either Hodges, Tres Ritos or Rio La Junta, or the pack trips to the Truchas Peak Lakes. There were always several of us on these trips but I was always the first to the stream and the last to leave and generally always the one with the largest catch of fresh water trout, cutthroat, rainbow and german browns. In those days the streams were not stocked as they are today but trout were more abundant.

Our fishing gear consisted of a size 10 hook, about 18 inches of leader and about six feet of fishing line and a couple of sinkers in late spring and early summer. In late summer and fall we replaced the size 10 hook with a couple of grey hackle flies. At any rate our "fishing" gear was rolled around our straw hat and when we got to the stream we would cut a long willow and fashion a fishing pole. In no time we dug for worms or caught some grasshoppers and we would be catching fish. It was considered sissified for any real native to purchase a license or to observe a limit. I would say that we probably did not know what the limit was. We just fished until we were ready to go home, keeping only the good-sized trout. Actually most of us could catch more fish without a hook, line or sinker during the spawning season. We did it with our bare hands under rocks or under logs in beaver dams. Occasionally we would pull out a water snake but that only made the day that much more exciting. Also part of the fun was observing a turista with his fancy fishing rod, automatic reel, hip boots, creel and what have you, getting his line caught in the brush in the stream. When we needed a fishing hook we just stayed close to a turista, he would get his hook caught and would either cut it or pull on the line leaving the hook embedded in the brush or log. We would wait until he moved on and presto we had yet another hook. Another place where turistas left their hooks was on branches of spruce and pine trees close to the stream. They were always making these wild casts with their full regalia of equipment and often times got their hook caught high up on a branch of a tree. Our hooks lasted for years as we almost never lost one. Of course, fishing without a license and with your hands and taking more than the limit was very much against the law, it was also muy macho, but we had not even heard the term yet. It was just the way life was.

I was already beginning to miss all this. I won't say anything about hunting mule deer or elk in the fall and winter as I do not wish to incriminate myself any further. Little did I know then that some day I would be a member of the American Wildlife Association and the Sierra Club, or that I would be working with Senator Clinton P. Anderson promoting his Wilderness Bills in the United States Senate, or that our daughter, Mónica, would be on the International Staff of the World Wildlife Fund in Washington, D. C. As I look back it would have been nice had I taken some time to smell the flowers along the way.

I said that Dominican Sisters ran the public schools in Peñasco. They did so until 1943. Then with the decree issued by the courts as a result of the Dixon Case in which the Presbyterian Church successfully challenged allowing teachers wearing a religious habit in the classroom, the Dominicans were forced to give up running the public schools in most of northern New Mexico. The Dominicans did a super job. I have always said that I am the product of a Dominican Sisters School but this is not a completely correct statement. My teachers were, for the most part Dominican Sisters and they wore the habit, and we said our prayers in school every day and we pledged allegiance to the flag and did all the things that students did in Dominican Sisters Schools elsewhere in the world. We also spoke English, but in the classroom only, outside the classroom and at home we spoke Spanish. If we spoke Spanish in the classroom we were whipped. If we went home and told our parents about it we got a second whipping at home. Woe be onto him or her whose parents found out about a whipping administered by Sister Norina who taught the fourth grade. She broke several rulers on my fingers! Somehow my mother found out each time and there went some more rulers! I was a very mischievous young man but Sister Maura, Superintendent, once told my mother that I was brilliant and that I should go to College.

College was something that was not even close to my mind on May 25, 1941 the day I graduated from Peñasco High School.

I had penned our class motto; "WINNERS NEVER QUIT, QUITTERS NEVER WIN!" but I actually did not know the meaning of it. It sounded good though!

Benedict Valdéz was finally through with his address, we got our diplomas and went home. There was a dance at Tom's that night. I did not go. I did not quite know about girls yet, although there were three in my graduating class who, I found out later, had designs on me. Instead I went home, to my little room in the attic, and got ready to leave home the next day. On May 26, 1941 I added two years to my age and enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps.

Now I really took time to smell the flowers.

I never returned home again except on short visits.

God Bless

America

By José Andrés "Andy" Chacón, DBA

Free Lance Writer & Ex-Adjunct Professor, UNM

Chicano Motivational Speaker.